We took a rare family road trip to the Adirondacks in late August, and it was as refreshing and exhausting as family vacations tend to be. Toward the end of our long drive home, even the kids were leaning forward in their seats urging my lead foot on. At that point in a road trip, even sixty-five miles per hour feels slow. We have become numb to our speed and numb to the road signs and farmstands that hurtle past.

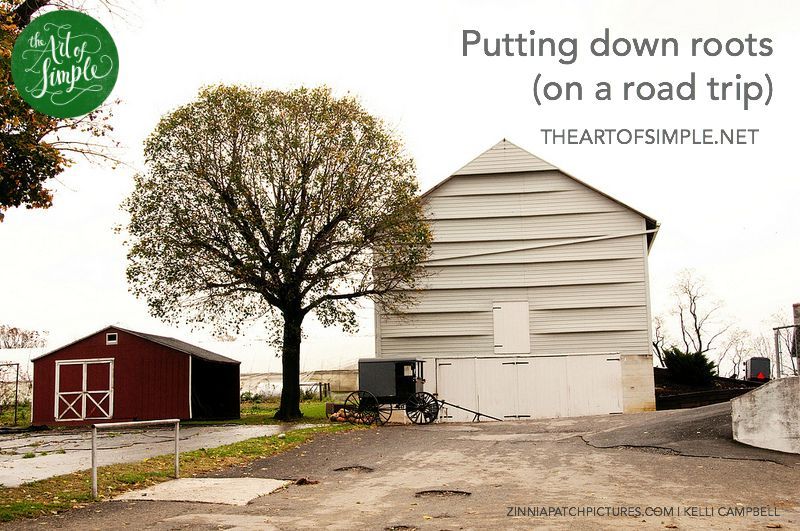

My family lives on the edge of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Only thirty miles from home, I hit the brakes, and we began to roll, slowly, behind the skinny wheels and somber black of a horse-drawn buggy. Our road trip ended at the pace of a horse.

For those few miles, we began to sit back again. We began to open our eyes again. We saw familiar green hills and that one farm with the best stripeless watermelons. I rolled down the windows, and we breathed again. Just-cut hay and a barn full of dairy cattle.

At five-miles-per-hour, you remember what you forget at sixty-five. You remember that you are in a place, even when you are moving from place to place. You remember the truth of Bilbo’s famous words, “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

I am a placemaker.

A homemaker, too, though that word is a little too close to stay-at-home-mom which isn’t really what I’m talking about. I do still have a young child at home, but when I say that I am a placemaker, I am speaking of my life purpose, not my season of life. I am also other things. A writer. A gardener. But, for me, those roles are wrapped up with the one big thing I want to do with the rest of my life: I want to cultivate a place and share it with others.

Our place, the one I make with my husband and four kids, is called Maplehurst. It’s a red-brick farmhouse built in 1880. It has quite a few bedrooms (those nineteenth-century farmers needed a lot of live-in help) and a few acres of land, and we love nothing more than to fill those bedrooms with guests and those acres with neighbors and friends. We grow vegetables and flowers, and we keep a baker’s dozen of egg-laying chickens, and, since we moved in three years ago, we have planted many, many trees.

Living holistically with my life’s purpose does not allow for much travel. I need to be here, feeding the chickens and watering the tomatoes. Any extra in the budget, and we spend it on trees rather than airfare.

To cultivate a place, we must stay put, and I mostly love to do exactly that. But I learned something at the end of our family road trip. Travel can help me in the task of caring for my own place. Travel, especially when I slow down and pay attention to the road between here and there, illuminates the connections between my place and all the other places.

When we moved to Maplehurst, we flew straight from Florida to Pennsylvania.

Only our furniture, with a stranger steering the way, followed the meandering highway from there to here. Six weeks after our move, I had our fourth baby. I think it took a year before I ventured much beyond our church and the grocery store.

I knew I had come home, but I didn’t really know where my home was. Now I know, in my mind and in my feet, that my home is tucked halfway between the ocean and the mountains. I know that these gentle hills are the roots of Pennsylvania peaks. I know that my driveway is part of a web of old Native American hunting trails, meandering creeks, and the wagon roads that once carried Quaker colonists.

Wendell Berry writes, “There are no unsacred places; / there are only sacred places / and desecrated places.” Traveling well, like living well, demands an attentiveness to the sacred qualities of every place on earth. When I travel, I would do well to slow down. I would do well to remember that even the road is a place.

But when I stay home, I must not forget the road that leads away from my own front door. To stay put is not to live a diminished life. All the love I plant on my green hill does not stay here. Like water, it runs on. It follows known paths and secret ones. It waters the trees I have planted and many I have not.