Keeping up with my monthly series in 2020 as a slow farewell to AoS, today I’m sharing another letter to myself in 2010, ten years ago. Each letter focuses on one of the different categories we write about here: relationships, community, work, travel, travel, and in the case of this month’s installment, self-care.

Though these are to myself, my hope is that you find a smidge of truth, beauty, and goodness you can apply to your own life — and perhaps this exercise will inspire you to write your own letters to yourself, ten years younger.

Dear Me in 2010,

When I first announced in January that 2020 would be this blog’s last year, after 12 years of consistent publishing, I thought it would be the longest year thus far in my writing life, that I’d finally say all the things I’ve wanted to say but kept tucked in my pocket, that I’d have all kinds of brain space to reflect and debrief about what AoS has meant to me the past decade-plus.

Of course, I didn’t know what 2020 would bring, and that with it, this blog’s last year would be an afterthought for me. Not that I wouldn’t care — I would, deeply — but that, like so many of us, much of my brain space and energy had to focus on a new way of survival.

So, here we are in October, and I can scarcely believe that in two months, I’ll be keeping just a few lights dimmed for those who want to continue reading the archives (of which there are many). And I’ll admit that it’s been hard to know just what to say here at AoS this year.

With all the everything around us (gestures widely), from the global pandemic and quarantine to our country’s election and everything in between, it’s been challenging to walk the tightrope of saying encouraging things without being trite, of saying things that need to be said without being another loud voice.

With two months left of keeping AoS an active blog, here are a few things I’ve learned about working well in a sort of year I never expected for its last one.

1. It’s okay to not be exceptional.

More than okay, actually. Many of us in our thirties and forties grew up with a notion that we needed to be remarkable and “live a big story” in order to make sense of our lives, to make a dent in our short time on earth. This idea is rampant in the world of entrepreneurialism, digital publishing, and self employment.

In order to stand apart in the fiercely competitive business world of the internet, you have to constantly scale your work — it has to grow, find new and more fans, and continually evolve to stay relevant. Boy, that’s exhausting.

It flies in the face of all the current advice about running a business, leadership, and digital platform growth, but I say it’s perfectly okay to be ordinary. In fact, some might say it’s a sign of mental health when you eschew the pressure to stand out from the crowd.

Every day on our Literary London trips we pause for a deep group discussion. So far this trip has been for women artists, entrepreneurs, and leaders, so the conversations revolve around the things these sorts would care about. A delightful Aussie was part of 2019’s trip, and she told us about a common idea in Australia and New Zealand that I still think about regularly. It’s called Tall Poppy Syndrome.

Essentially, it’s the idea of disparaging someone for choosing to elevate or rise above the expectations of their peers. Being a “tall poppy” is negative because it’s seen as thinking too highly of yourself.

In my mind, being a tall poppy is both negative and positive, in that it promotes egalitarianism yet it can also discourage reaching one’s full potential. But I think it’s interesting that this is even the widely-held belief of a culture because I can’t think of anything more opposite to the American mindset of overachievement.

Here in the States, we are infused with the idea of being tall poppies, and to not want to be a tall poppy is to settle for ordinary. This year more than all my other years of writing online (but it’s gradually been coming the previous three or so), I’ve learned to embrace being an average-height poppy.

If being an ordinary poppy means not being a slave to continual growth, obsessing over metrics, and feeling like I always have to say something and constantly post, I’ll take it. I’ll be over here, blooming just fine.

2. Our metrics for success are really odd.

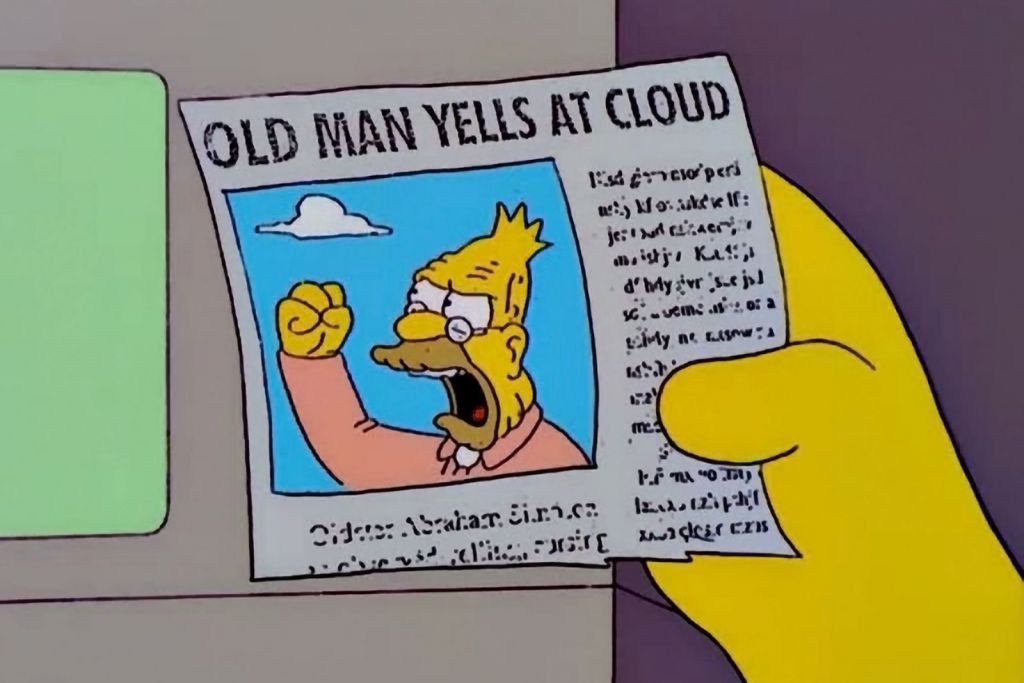

I won’t spout again my current feelings about social media, because it makes me feel like that “old man yells at cloud” Simpsons thing. If you read my newsletter or follow me pretty much anywhere on the internet, you already know I side-eye its role in our culture.

But only recently I had this realization: the metrics of social media are also just …weird. It really is. For us to ask our business leaders, politicians, artists, writers, or any other sort of community member to publicly say something witty, important, pithy, funny, groundbreaking, controversial, comforting, or wise at regular, near-daily intervals — and then for us to “vote” on them with thumbs and hearts and for us to measure its success on that number displayed — is a strange way to decide what’s important in our society.

Yet we do it all the time. And it can really mess with our heads. It was rumored not too long ago that certain platforms like Instagram were toying with the idea of hiding numbers publicly, and I am such a fan of that concept, yet I don’t see it happening right now. Not sure if it’ll come to fruition.

Regarding work, and specifically in my line of work of mostly writing, it’s not just the idea of whether social media is morally good, evil, or neutral — it’s also the idea that it’s distracting.

Yes, it’s good to cultivate and communicate with an audience that likes your work. I’m so grateful social media has helped me do what I do (though it doesn’t hold as powerful a place as it purports itself to have). But its never-ending-ness and its screams for attention pull so many well-meaning artists away from doing the things they’d truly rather do: create something that stands the test of time.

I like social media when it allows us to talk to each other. I loathe it when it keeps score on who matters based on how addicted they are to it. This year, I’ve chosen to give it less attention, and I’ve paid a bit for it. I’m hedging my bets, though, that my work will be better off in the long run.

3. We all need art.

In all this entrepreneur-ing and creating and publishing, we still long for beauty in our lives, and we’ll pay the price if we focus too much on content-creation for other people without savoring art ourselves.

Work daily, yes, work smart and hard, and do the thing you’re meant to do — of course. I’m all for that. But stop every day, and just enjoy life. Always carry a novel with you so you have something to do besides the anxious scroll. Light a candle or listen to music as you work, so you remember checking off your to-do list isn’t all there is. Go on a walk every day so you make sure you daily step on crunchy leaves and look at grass and trees and maybe a neighbor.

Work well, and then be done with it, and take care of yourself with a regular, daily dose of art of all types. You’re not a machine. You don’t exist to check off a to-do list. The purpose of your life is not productivity.

These are the work-related things I’ve learned in the last year of this blog, perhaps more than anything else.

Love,

You in 2020